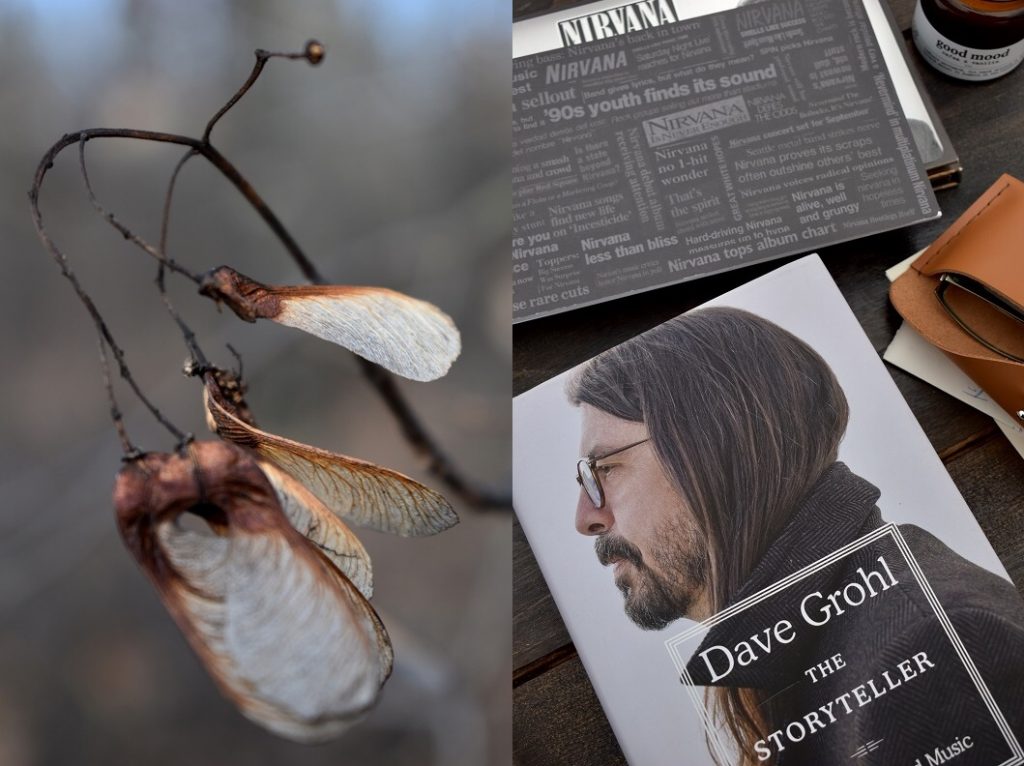

Photos: Classiq Journal

”Because I still forget that I’ve aged. My head and my heart

still seem to play this cruel trick on me, deceiving me with

the illusion of youth as I greet the world every day through

the idealistic, mischievous eyes of a rebellious child who

constantly seeks adventure and magic. I still find happiness

and appreciation in the most basic, simple things.”

Dave Grohl

I have been waiting for a Dave Grohl book, without knowing he was writing a book, and without realising how much I needed to read his own story, as well as the only story I have ever wanted to read revolving around Nirvana. Ever since he started his own band, Foo Fighters, 28 years ago, Dave Grohl has been much more than “that guy from Nirvana”, even though he admits he would be proud if that were the case – “Those three and a half years that I knew Kurt, a relatively small window of time in the chronology of my life, shaped and in some ways still define who I am today. I will always be ‘that guy from Nirvana’, and I am proud of it. […] I knew deep down that nothing would ever compare to what Nirvana had gifted to the world. That sort of thing only happens once in a lifetime.” The Storyteller: Tales of Life and Music is a love letter to music and to a life dedicated to music, but also to finding the thing that you love doing and living for it, because apart from family and friends, that’s where you find guidance, counseling, love, hope, belonging.

“What was once my life’s greatest joy had now become my life’s greatest sorrow, and not only did I put my instruments away, I turned off the radio, for fear that even the slightest melody would trigger paralyzing grief. It was the first time in my life that I rejected music. I just couldn’t afford to let it break my heart again,” he writes about his feelings after Kurt’s death. Humbleness in musicians is not that easy to find, and only great people have it.

And it’s the way he speaks of Kurt… the only way the whole world should remember him. Why is this the only story I have ever wanted to read about Nirvana? Because making personal perception of a person a significant part of anything and everything ever written about him without the slightest constraint, without enough hindsight to keep from making his death a defining part of his life, is the easy way, and easy is the way much of the world goes for. I am not interested in that. Dave’s is the most touching and sincere tribute.

“And Kurt.

If only he could have seen the joy that his music brought to the world, maybe he could have found his own. My life was forever changed by Kurt, something I never had the chance to say while he was still with us, and not thanking him for that is a regret I will have to live with until we are somehow reunited. Not a day goes by when I don’t think of our time together, and when we meet in my dreams there’s always a feeling of happiness and calm, almost as if he’s just been hiding, waiting to return.”

Nirvana’s music seamlessly found its way into my life, not in an abrupt way in my teens, but in a subtler, more consistent way throughout the years. But it always harkens back to those years of what seemed like aimless wandering, trying to make peace with not belonging in the most popular groups, or later on, in the crowds of trenches trying to find a pre-defined notion of success in the safety of a nine-to-five job. And it always makes me smile.

Viewing

The French Dispatch, 2021

If I could sum up Wes Anderson’s latest film, I would say: Play is a serious thing. His signature filmmaking style – the playfulness and precision with which the objects and narratives are arranged, the use of set design, camerawork, stop motion, the alternation of black and white and colour, of animation and live action, are a guarantor of authenticity of film as a work of art – seems to have reached a new level. The French Dispatch brings to life a collection of stories from the final issue of an American magazine published in a fictional 20th-century French city. In a recent interview, Bill Murray, a long-time Wes Anderson collaborator, says about their first film together, Rushmore: “He was just a kid, but he was also a guy who knew what the hell he was doing and what he wanted to do, right from the beginning.”

Il ferroviere, 1956

Postwar Italy seen through the eyes of a poor railroad engineer, father and husband, Andrea Marcocci (Pietro Germi), who sees his family crumble within a society that goes through fast economical and social changes. It’s both moving and realistic, and that’s largely because the story is also seen through the eyes of 8 year old Sandro (Eduardo Nevola). Director Pietro Germi, whose neorealist films I have always liked more than his acclaimed late comedies, tells great truths through great simplicity.

I have been on a Bertrand Tavernier film marathon (four of which follow below). I have to admit that I had seen few films of his until recently. I had known more about his work as a cineaste, further fueled by the extraordinary book released earlier this year, Amis américains: Entretiens avec les grands auteurs d’Hollywood, than about his films. But now I have become hooked on his films. “All my films are about subjects that I know little about but wish to discover. For me, film is an exploration in which I am going into a semi-unknown country to share with people I do not know the things that make me laugh and make me angry. I do not like films that are like organised tours,” said Tavernier in an interview with Jason Wood from 2002. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I love his films. There’s always something new to discover in each of his films, you want to understand that world, not just look at it from afar, from the comfort of your seat.

L.627, 1992

One of his first films dealing with contemporary social ills and issues in France, offering a timely observation on drug abuse. Watching L.627, whose title refers to an article of the Public Health Code prohibiting the consumption and trafficking of narcotics, I realised it may have been an inspiration for Maïwenn‘s Polisse (2011), a shockingly realistic chronicle on the daily life of an investigation group of the Parisian Brigade for Child Protection. The subject is different, but the incredibly realistic and piercing way the two police brigades and their very specific behaviour and sense of humour are depicted, are very clear similarities between the two films. Because it is above all the description of a group (not of the police force as a whole and the politics behind it), how it functions, how it evolves in everyday life, how they cope with the harsh realities of their job. It feels like Tavernier did not use any artifice in the way he filmed, just instinctively recording what he saw.

Ça commence aujourd’hui (It All Starts Today), 1999

Bertrand Tavernier was a great observer of society. He also had the humanity to observe it with understanding. He proved it in L.627, and again in Ça commence aujourd’hui, a social drama revolving around the efforts of a schoolteacher (Philippe Torreton) to bring change to his demoralised, largely impoverished community after the coal mine in the village closes down.

Un dimanche à la campagne (A Sunday in the Country), 1984

An aging father welcomes his children and grandchildren for a Sunday at home in the countryside. But it’s the affection that Tavernier lends the father-daughter relationship that stands out, such a beautiful portrait of a parent-child deep bond, beyond words, just through mere looks, that can instantly reignite after a long time apart. Watching this film can be such a bittersweet, ravishing experience, for anyone living apart from but who has had a beautiful relationship to his parents, but especially grandparents. For every visit, even if it lasts a day or just a few hours is met with unprecedented joy and no reproachful words, and with just a saddened, smiling sendoff after the visit that can take you back and forth your entire life in the blink of an eye, a bridge between the hopes for the future and the nostalgia for the past.

In the Electric Mist, 2009

In an interview for Cineaste after the film’s release, Tavernier said about the novel his film was adapted from, In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead, and its writer, James Lee Burke: “I like his style, the melange of introspection, lyricism, description that is very meditative and beautiful and then, of course, the dialog. I find Burke a writer of genius when it comes to dialog. He knows how to evoke the character in a few phrases. He writes romans noirs in which characters come before the intrigue.” The film has this meditative beauty and noir darkness, too. Tommy Lee Jones’ character, Dave Robicheaux, is a man of integrity but with dark sides, who has his doubts, questions, and his own past demons, and in which, in turn, make him human, vulnerable, flawed, relatable. And the Louisiana we discover is different than what I have seen in American films (and I wouldn’t be surprised if it were among the most accurate depictions of the place), it has something mystical in it, both fascinating and dangerous. And yet, Tavernier made it clear that he “didn’t want to show it as a French director. I wanted it to be as seen through the eyes of Dave Robicheaux. You discover a country through the eyes of the people who live in it.” And there is Buddy Guy on the soundtrack (and he also appears in the film), a soundtrack that deserves a stand-alone mention. The film makes indeed great use of the music, light, history and characters that are inextricably linked to Louisiana.

Moby Dick. One chapter a day, the best piece of advice I have received about re-reading this book after so many years. There was a time when, for one reason or another, I didn’t read fiction anymore. I read everything else but fiction, from essays to autobiographies, from history books to film commentary. When I asked my favourite bookstore owner what he would suggest, he said: “We simply have to search, all the more so if we have distanced ourselves from fiction, and find a text that can be anything – a haiku, a poem, a SF, a collage or a classic novel – that will wake us. I don’t have any other solution. What I know for sure is that – it sounds like a banality, but it never hurts repeating – reading, especially fiction, is an activity that must be exercised daily, just like physical exercising, otherwise we go numb.” Moby Dick is the book that would wake me.

My interview with photographer Laura Wilson, a frequent collaborator of Wes Anderson. “I’ve known Wes since he was an undergraduate at the University of Texas, and because of his friendship with my sons, Andrew, Owen and Luke, and with us, my husband Bob and I, we have a special bond. I was the first person to photograph Wes when he began in film as the director on Bottle Rocket, and he has remained loyal to me for many years.” We talked about her portraits of the great American West, her work with Richard Avedon, about photographing Wes Anderson’s films and Hollywood royalty.

Listening

Buddy Guy for In the Electric Mist. Foo Fighters, The Colour and the Shape.

In order to keep his hearing trained during the pandemic, composer Alexander Liebermann started to transcribe the sounds of animals and birds into partitions: The Birdsong Collection, Songs from the Sea, and Various Animals. There is nothing more therapeutical than the sounds of nature.

Exploring

Plăiuț is the most playful and creative travel guide for children I have seen, perfect for their curious and adventurous minds. Accompanied by a traditional map, it’s the most beautiful way of discovering a country for children, parents and grandparents alike.

The regulars: The interviews, newsletters and podcasts I turn to every week and/or every month because they are that good. Craig Mod’s all three newsletters: Roden, Ridgeline, and Huh. Wes Del Val’s book-ish interviews. Soundtracking, with Edith Bowman. Team Deakins, with Roger and James Deakins. Alicia Kennedy’s newsletter. The Adventure Podcast: Terra Incognita. Monocle and Sirene magazines, in print.

“We had always been the outcasts.

We had always been the weirdos.

We were not one of them.

So, how could they become one of us?”

Dave Grohl