”The Tree of Life”, 2011 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © Fox Searchlight Pictures

By the very nature of photography, you have to get in close in order to get a good picture. But on a movie set, that can become a very challenging job and to do it well can be extremely difficult. That’s the job of the film set photographer. Because a good unit still photographer must get close while remaining unseen, is ever-present yet invisible, incredibly quiet and gentle, yet forceful and determined. They may be obliged to keep the distance, but they must know how to be in the right place at the right time, which is everywhere and at any given time. And so not only do they require technical skill, but they must know and respect film and possess a keen understanding of human behavior and patience. And they wear black and hide so that they record not only the situation that is presented to them and document the film as it’s being made, but also capture the moment. That moment of intensity, of an actor immersed into a role, or that moment of earnestness and contemplation between takes that makes the viewer forget that a film is being made and seems depicted from life itself, not a still-frame of what’s seen on screen but something much more real and authentic, before the editing and special effects come into play. It’s not just about the image, but about the feeling.

Merie Weismiller Wallace is the unit still photographer of so many great films, from Mystic River and Titanic, to The New World and Nebraska, and her beautiful work in cinema is a great reminder that making a film is truly a team work. In our interview, I am talking to Merie about the uniqueness of her job, about how it is like to work with Clint Eastwood, Terrence Malick and Alexander Payne, about the The Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers, and about the importance of putting the camera down sometimes and participating to life instead of watching it.

Clint Eastwood on the set of “Flags of Our Fathers”, 2006, Iceland | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace

© Warner Bros. Pictures

Many filmmakers are very particular about the set photographers they allow to document their work. You have repeatedly worked with Clint Eastwood and Terrence Malick, who are well-known for their close and loyal team of collaborators. What is it that gained you their trust?

I believe I gained their trust by being professional and authentic, as they are. They don’t go for pomp and circomstance. And I believe they could see that I take my job with true inspiration as I capture all the collaborative contributions – while still remaining attentive to taking still photographs for Publicity, Advertising, and Archiving.

Do directors usually let you take initiate or do they tell you what they want you to photograph?

Directors rarely tell a Unit Still Photographer what to photograph, unless they see something exciting and they call us over to catch a shot they like. Generally, the only people who tell set photographers what to shoot are the Studio Publicity Department photo editors who read the script and know what shots they want to publicize for the project. However, they too generally let us take our own initiative. We know what is needed, we know how to get it, we know when something remarkable is unfolding, and we know when we need to step back because of personalities or time constraints.

In this regard, how difficult is it to get close while keeping your distance?

Set Photographers do have to remain quiet and unseen, but that is also a bit of a prejudice, we are no different than the boom person, dolly grip, or focus puller; we have a job to do and must do it without being distracting to the cast or other highly focused crew such as the camera operators and director. That goes without saying, it is par for the course. Where the difference is, is that Stills are not required to make a movie, they are required to sell one; so we are guests in that way and yet must become part of the fabric of the set. Also, some people are camera shy, they are distracted by a still camera in a way they are not distracted by a sound microphone. So we must be subtle, unnoticed, while still getting the dynamic shots that the motion picture camera is getting. There have been countless times I was painfully aware of myself and where I had to be to do my job during highly sensitive scenes – that is the story of our profession. We pick our positions, we pick our lenses, we wear black, we move slowly, and we hope the actor can ignore us as they do the rest of the on-set crew.

Saoirse Ronan in “Lady Bird”, 2017 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © A24 Pictures

”When a set photographer is trusted,

we are ignored, and then our true abilities

and personal creativity are free to flow.”

There was a time when film set photographers were asked to take a photograph of a scene that had just been shot by positioning their camera in the same spot as the film camera, and to leave immediately afterwards to avoid delaying the work of other technicians. But the role of a unit still photographer has become much more important than that. How do you yourself approach set photography?

Let me say that many photographers consider ourselves lucky if we get to put our cameras where the motion picture camera was, because we rarely get that magnificent angle otherwise! That being said, that is not our job. Our job is to capture the moments of a performance live, during a take as it is unfolding, and it is never, never the same if they hold the set and actors pose for stills. I approach set photography as a witness and an admirer. I watch everything, every moment performed, how the light is falling, how the crafts such as wardrobe, make-up and hair are also telling the story. When we are rolling, I am capturing what the actors are giving as well as the director’s, production designer’s and cinematographer’s visions. Between takes I am watching as the world is being made, the people standing-by as well as those stepping forward in the instinctive choreography of collaboration. When a set photographer is trusted, we are ignored, and then our true abilities and personal creativity are free to flow, and we do our best work.

Do you know immediately when you have taken a good picture, maybe that very photograph that captures the essence of the entire film? Is there a split second when you press the button and you know you have made the shot?

I know when I have seen something remarkable, and that I was in tune and captured the moment. As unit photographers, we lay in wait, watching for the moment when a tear glistens, or mist engulfs. We are poised and atuned, and we know when we have caught a moment as surely as we knew it fleetingly existed.

And then there are shots that show the scale of the set you are working on, like this one from Midsommar (ed. note: image below). The bird’s-eye view evokes this feeling that you inhabit a silent world where you are on your own just watching. And I think that just shows how special the job of the set photographer is.

Films use enormous crane arms for sweeping shots that show the scope of a scene and the emotion of the move, often from wide establishing into the eyes, heart and soul of an actor’s performance. In this shot I asked the generous Grip Department if they would give me their tallest ladder in a position similar to the wide establishing, but just out of their way. Sometimes we are not able to make such a request, because of the impact on the department in the rush of work, but this time I was. It was marvelous being up for a take or two and solitarily watching all the puzzle pieces fall into place. Then I climbed down and went closer for the performances in later takes. When I watch those crane arm shots on the monitor I always wish I could fly!

”Midsommar”, 2019 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © A24 Pictures

How often does it happen that the filmmakers and studios choose the images you yourself would have picked to represent the films? Does your idea of what represents the film often differ than theirs or do you often find yourselves on the same page?

I know what type of imagery is needed to publicise a film, and I almost always know which images they will use. We understand genre, we capture the essence of stories and theatrical tone to tell or publicise the story. However, those images are usually not my favourite images from a project. That is why it is so wonderful to exhibit with the Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers: We have the oportunity to show our favorite images, serendipity moments often not suited to a Press Kit.

You were president of the Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers for four years and you are still co-chair of the SMPSP Exhibition Committee and Archive Committee. Could you tell me more about the organization? How important is it to be there and what was your biggest accomplishment during your tenure?

The Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers was founded in 1995 as an honorary organization dedicated to the art of motion picture photography. We pursue exhibiting our favourite images to promote our interest in proper archival preservation of set photography for its intrinsic artistic, historical and cultural importance. To become a member one must have worked as a dedicated unit still photographer for a minimum of eight years, and to show artistic excellence beyond standard craftsmanship; there is a rigorous application consideration process. I had a marvelous four years as SMPSP President recently where we reached out to Studio archivists, promoted exhibitions across the country including three at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in their Mary Pickford Center for Motion Picture Studies, revamped our website to present us clearly and creatively, and worked on committees for outreach and member support.

You have documented so many great films, from Mystic River, Strange Days and Million Dollar Baby, to The Tree of Life, Nebraska and Lady Bird, and each must have been an extraordinary experience. But has there been any particular movie when you felt, during its filming, that you were witnessing something truly special?

Actually, on every movie you listed I felt that way, as I have watched through my lens cinematic history being made. And to your list I will add Sideways, The New World and Titanic. Sideways was an odyssey of humour and human failure, and shooting it became a celebration of capturing director Alexander Payne’s uncanny vision and comedy of farce. The New World was a gorgeous period piece where the wardrobe, lighting and production design were destractingly photogenic – but then in that context, the performances of Colin Farrell and Q’orianka Kilcher were so passionate and arresting that I could not stop shooting the spontaneous moments Terrence Malick inspired.

Q’orianka Kilcher in ”The New World”, 2005 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © New Line Pictures

Photographing Titanic was tanamount to living in and capturing a lightening storm. Scene after scene I was swept away by Kate and Leo’s honest, profound, and enchanting performances, by camera operator Jimmy Muro’s uncanny skill in capturing the dynamic world Director James Cameron brought to life. Titanic was an ovation of masterful story telling and pushed the envelope in all departments.

Nebraska was filmed in black and white. Do you think this beautiful form should be more present in contemporary cinema or are there certain stories that seem to lend themselves to being made in black and white?

On Nebraska it was made very clear from the beginning that no colour images were to be released – and I was so excited for that rare opportunity! These days, black and white photography in film-making and set photography is a rare creative choice. And because it is now an option with digital files, the Studios want all set photography in colour, and then they can adapt the file and printing to black and white as needed. As artists, photographers – and cinematographers – love to work in black and white because it conveys imagery in such a striking, stylistic way. Some moments and images we just see in black and white. Others you shoot in colour and secondarily adapt to black and white, play with the greyscale, hard blacks and mixed tonalities; it’s a joy to work with! I believe the Studios are afraid that black and white represents the past, and that modern viewers won’t be interested. I believe that is financial thinking, not creative, and underestimates the power of black and white and the creativity of the audience.

”Good set photography is both creative and witnessing.”

Bruce Dern in ”Nebraska”, 2013 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © Paramount Pictures

Some of the pictures taken by a still photographer are used as film posters. What makes a good movie poster?

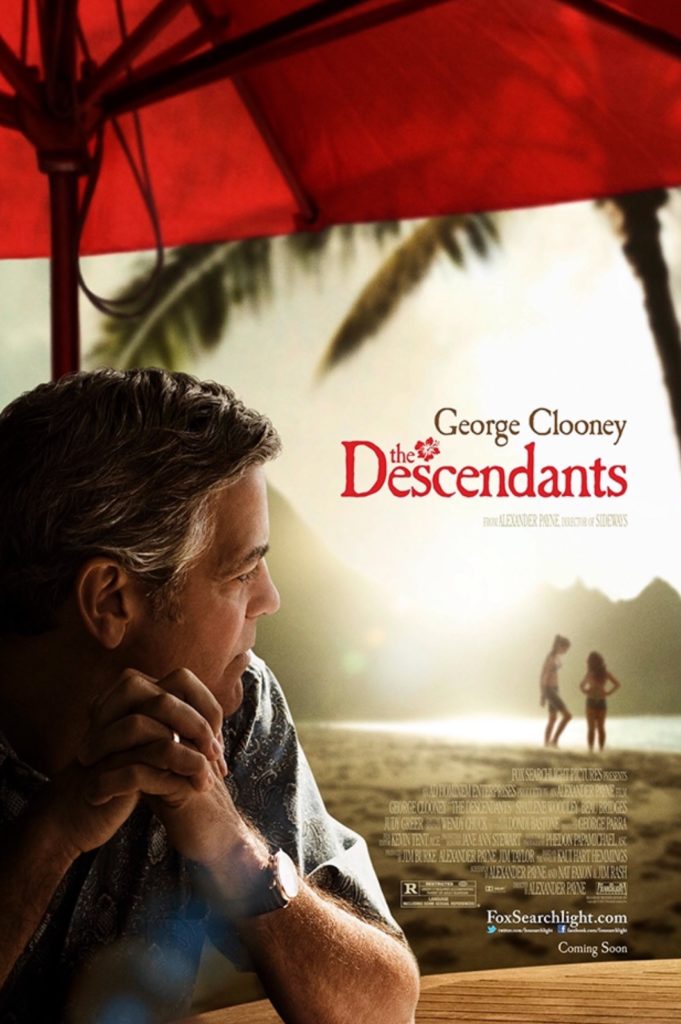

A good movie poster is full of the pathos or mirth of the project, is visually dynamic, and presents the subject in a way that invites audience curiosity rather than giving away the punchline or plot twist.

With movie posters, I like it when they use my set photography rather than an organized advertising shoot where the actor looks perfect and is looking into the camera at the viewer. Set photography captures the performances the director inspires, the actors give from the heart and soul, in the lighting the DP intended, in the context the production designer creates; so those moments really tell the story of the film if picked and presented artfully by the Studio Advertising departments.

”The Descendants”, 2011 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © Fox Searchlight Pictures

Raymond Cauchetier, the photographer of The French New Wave, said: “Artists are creators. I am a witness.” Do you agree?

Some photography requires witnessing and documenting, the astute photographer sees things most people pass by unoticed. Some photography is creative such as when the photographer throws their creative perspective into the mix through lens choice, camera angle, subject-focus; and then some creative photographers light and direct their subjects as well for a purposeful portrait. Good set photography is both creative and witnessing: We have our own creative instincts and abilities which we bring to the table to best capture the artistry presented by the world’s leading collaborative filmmakers.

David O. Russell on the set of ”Joy”, 2015 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © 20th Century Fox

How predictable or unpredictable is the encounter between you and your subject when you do a portrait?

There are spontaneous portraits, and then there are posed portraits. Set photographers’ portraits are generally seized moments, so for us it is completely unpredictable. I get an instinct for character very early on when I meet someone, and that is what I generally shoot for in a portrait. I look at the colours they have chosen in their clothes, I look at jewellery and wrinkles, is their hair brushed, what book they are reading, how old are their shoes. It’s great to get to know someone, but often we don’t have the leisure to do that. More so I try to put the person at ease, and let them give me who they are.

What is the biggest misconception people have about Hollywood?

That it’s an actual place you can visit. It is not. Hollywood is an Industry, and it only materializes when all the parts of a production are in place for the fleeting time between Rolling and Cut, between Day One and Picture Wrap.

”It was like Alice through the Looking Glass,

I’ve been shooting ever since.”

Do you always carry a camera with you?

I go through phases. For years I always carried a camera, and often I still do, but one can get lost behind a camera, watch life instead of participating; so now I am careful to put my camera down sometimes and get into the splashes of life.

How did you first fall in love with photography?

I was in Borneo, Malaysia, supervising a 2nd Unit shoot on a feature film called Farewell to the King written by John Milius and starring Nick Nolte and Nigel Havers. The Unit Still Photographer was busy on 1st Unit, so when asked, he said “You do it!” So I did, and it was like Alice through the Looking Glass, I’ve been shooting ever since. In fact, I took everything I earned on that film and went to Singapore on the way back to the States and bought a full Camera set-up to pursue the career! I had gone to USC Film School just before that and gotten an MFA in Film Production, so I thought shooting Stills on set would just be a way to support myself while I continued to learn about Production and continued my goals of screenwriting. But with persistence, my career as a photographer took off, and I ended up just riding the wave.

Have you considered picking up screenwriting again?

For me, writing and photography are somehow mutually exclusive as if it is a right-brain, left-brain conflict: As long as I am shooting individual frames, my mind does not tell me stories. For now, I am still lost in the Wonderland rabbit hole of photography, with no plans for, or against, writing in the future.

Sean Penn in ”The Tree of Life”, 2011 | Photograph by Merie Weismiller Wallace | © Fox Searchlight Pictures

Website: meriewallace.com

The Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers: smpsp.org

More stories: The Art of Film Posters: Interview with Illustrator Tony Stella / Production Designer François Audouy Takes Us Behind the Scenes of Ford v Ferrari / La enfermedad del domingo: In Conversation with Costume Designer Clara Bilbao

6 Responses to On and Off Set with Unit Still Photographer Merie Weismiller Wallace